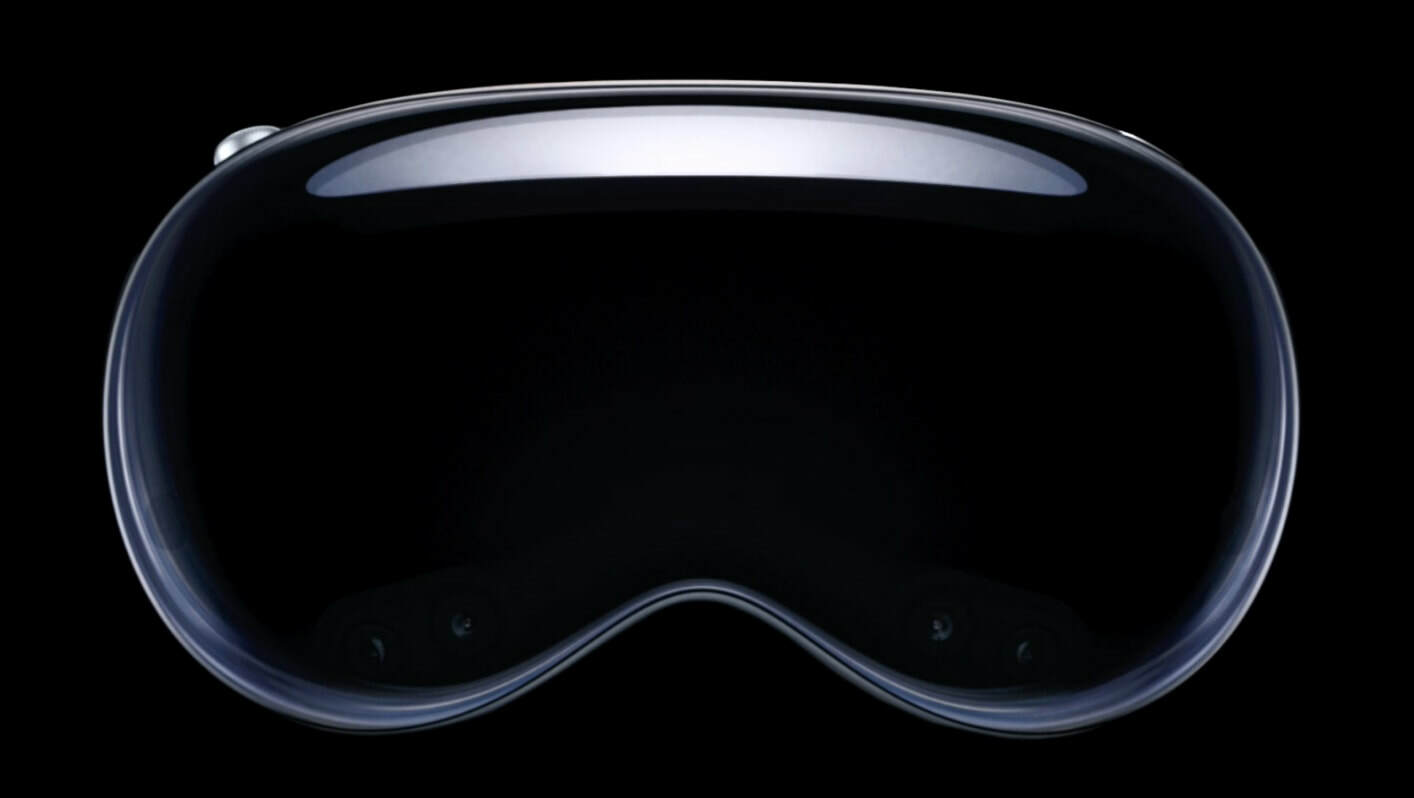

At a time when the world is captivated by the social impact of AI and ChatGPT, Apple's launch of the Vision Pro, its first 3D glasses, passed almost unnoticed last week.

"It's a technological marvel," wrote the authoritative weekly The Economist, though not really known for using hyperbole in its commentaries. Apple proves once again that a brand does not have to be a technological pioneer to reach market leadership in a sector. And as usual, the Cupertino-based company isn't embarrassed to put a $3,500 "premium" price tag on the Vision Pro glasses. Apple users love a dash of prestige and exclusivity, and that may/should have a price.

In technology circles, but also in broad circles of business leaders and management consultants, not to mention in the media, it has long been assumed, for decades even, that companies that succeed as pioneers in bringing a new technology to the market will therefore have a competitive advantage for a long time to come (in the management literature this is sometimes referred to as the first-mover effect).

But a number of scientific studies clearly show that this theory is wrong. For example, the American researchers Tellis and Gordon set up a large-scale study in which they examined more than 650 products from 66 different categories. [i] More specifically, they compared the frontrunners in the various branches in 1923 with the frontrunners in 2000. The conclusion was clear: a whopping 64 percent of those who enter the market first fail... And those who don't fail have barely 6 percent market share. Only in 9 of the 66 categories were the original pioneers still leaders and in recent years that score has decreased (1 in 16 from 1974). On average, a pioneer retains his leadership position for five years. Moreover, the current market leaders entered the market on average nineteen (!) years later than the pioneer.

Tellis and Golder have shown that many companies that are now market leaders are also seen as the pioneer. But in fact, they are often quick followers, and the original pioneer has long since left the market.

So we can safely say that the statement about the first-mover advantage can be strongly relativized. But that doesn't mean innovation is unimportant. Or that pioneers cannot be market leaders in the long run, although this only applies to a small minority. Brands must innovate: it gives them the necessary oxygen to retain existing customers and win new ones and strengthens their leadership position. Innovation also ensures that the focus is on the value of a product and not on the price, and moreover, innovation gives a purpose to the organization: it keeps them on their toes and reminds them that once you have taken the step to the market, you must always keep innovating.

There are, of course, many types of innovations. In Apple's case, its innovative strength is said to be primarily in the way the company approached the market. Apple usually didn't do that first, but as a smart or fast follower. Many current market leaders – even those with an innovative halo – are in reality smart followers. While the real pioneers are long gone.

The Apple case therefore frequently illustrates the theory of the pioneer versus the smart follower: both in a positive sense (due to the successes from iPod to iPhone) and negatively (when the company failed due to the fact that they entered the market too quickly without taking into account the wider environment).

Will history repeat itself again with Apple's Vision Pro?

[i] Tellis, G.J. & Golder, P.N. (1996). First to market, first to fail? Real causes of enduring market leadership. Sloan Management Review, Winter, pp. 65-75.

Tellis, G.J. & Golder, P.N. (2006). Will and vision. How latecomers grow to dominate markets. Los Angeles: Figueroa Press.

Written by BBDO Belgium Team, We create effectiveness